This article is part of our Business Startup Guide—a curated list of our articles that will get you up and running in no time!

First, allow me to deal with a very common problem: Business owners are often afraid to forecast sales.

But, you shouldn’t be. Don’t think there is some magic right answer that you don’t know. Don’t think that it’s a matter of training you don’t have. It doesn’t take spreadsheet modeling (much less econometric modeling) to estimate units and price per unit for future sales.

It isn’t about seeing into the future

Sales forecasting is much easier than you think, and much more useful than you imagine.

It’s not about guessing the future correctly. We’re human; we don’t do that well. Instead, it’s about assumptions, expectations, drivers, tracking, and management.

You review and revise your forecast regularly. Since sales are intimate with costs and expenses, the forecast helps you budget and manage. You measure the value of a sales forecast like you do anything in business, by its measurable business results.

I was a vice president of a market research firm for several years, doing expensive forecasts, and I saw many times that there’s nothing better than the educated guess of somebody who knows the business well. All those sophisticated techniques depend on data from the past—and the past, by itself, isn’t the best predictor of the future. You are.

That also means you should not back off from forecasting because you have a new product, or new business, without past data.

New product or not, your sales forecast won’t accurately predict the future. We know that from the start. What you want is to lay out the sales drivers and interdependencies, to connect the dots, so that as you review plan versus actual results every month, you can easily make course corrections.

If you think sales forecasting is hard, try running a business without a forecast. That’s much harder.

Your sales forecast is also the backbone of your business plan. People measure a business and its growth by sales, and your sales forecast sets the standard for expenses, profits, and growth. The sales forecast is almost always going to be the first set of numbers you’ll track for plan versus actual use, even if you do no other numbers.

If nothing else, just forecast your sales, track plan versus actual results, and make corrections—that process alone, just the sales forecast and tracking is in itself already business planning. Even if you do nothing else.

Step 1: Plan your streams

Plan how many streams of revenue you have. Look for the right level of detail. Forecasting, even though it often results in tables that look like accounting reports, doesn’t work in too much detail.

For example, a restaurant ought not to forecast sales for each item on the menu, but for breakfasts, lunches, dinners, and drinks. And a bookstore ought not to forecast sales by book, and not even by topic or author, but rather hard cover, soft cover, magazines, and maybe main sections (such as fiction, non-fiction, travel, etc.) if that works.

Always try to set your streams to match your accounting, so you can look at the difference between the forecast and actual sales later. This is excellent for real business planning. It makes the heart of the process, the regular review and revision, much easier. The point is better management.

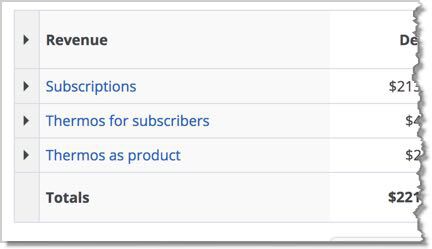

For instance, in a sample plan for Soup There It Is, soup delivery to offices at lunchtime, the sales forecast foresees three lines of sales, as shown below.

On this sample case, the revenue includes monthly subscriptions, which include multiple lunches delivered during the month; a thermos product sold to subscribers at a steep discount; and the thermos product sold to nonsubscribers. The bookkeeping for this startup tracks sales in those same three categories.

Step 2: Forecast row by row

There are many ways to forecast a row of sales.

The method for each row depends on the business model

Among the main methods are:

- Unit sales: My personal favorite. Sales = units times price. You set an average price and forecast the units. And of course, you can change projected pricing over time. This is my favorite for most businesses because it gives you two factors to act on with course corrections: unit sales, or price.

- Service units: Even though services don’t sell physical units, most sell billable units, such as billable hours for lawyers and accountants, or trips for transportations services, engagements for consultants, and so forth.

- Recurring charges: Subscriptions. For each month or year, it has to forecast new signups, existing monthly charges, and cancellations. Estimates depend on both new signups and cancellations, which is often called “churn.”

- Revenue only: For those who prefer to forecast revenue by the stream as just the money, without the extra information of breaking it into units and prices.

Most sales forecast rows are simple math

For a business plan, I recommend you make your sales forecast a matter of the next 12 months and the two years after that.

Start with units if you can

For unit sales, billable hours and revenue only lines of sales, start by forecasting units month by month for the first year, as shown here below for the thermos-for-subscribers line of sales in the Soup There It Is plan:

I recommend looking at the visual as you forecast the units, because most of us can see trends easier when we look at the line, as shown in the illustration, rather than just the numbers. You can also see the numbers in the forecast near the bottom. The first year, 2019 in this forecast, is the sum of the months.

Estimate price assumptions

With a simple revenue-only assumption, you do one row of units as shown in the above illustration, and you are done. The units are dollars, or whatever other currency you are using in your forecast. In this example, the thermos-for-subscribers product will be sold for $9.95, but for forecast purposes, it’s rounded to $10.00 even.

Multiply price times units

Multiplying units times the revenue per unit generates the sales forecast for this row, as shown here below. In April, you see 15 units times $10 per unit is $150. In May, 60 units times $10 is $500.

Subscription models are more complicated

The Soup There It Is plan includes a subscription forecast for its first row. For subscriptions, you normally estimate new subscriptions per month and canceled subscriptions per month, and leave a calculation for the actual subscriptions charged. That’s a more complicated method, which demands more details. For that, you can refer to detailed discussions on subscription forecasting in A Complete Guide to Forecasting Sales For Your Subscription Business and 5 Metrics You Need to Track Your Subscription Forecast on this site.

But how do you know what numbers to put into your sales forecast?

The math may be simple, yes, but this is predicting the future, and humans don’t do that well. Don’t try to guess the future accurately for months in advance.

Instead, aim for making clear assumptions and understanding what drives sales, such as web traffic and conversions, in one example, or the direct sales pipeline and leads, in another. Review results every month, and revise your forecast. Your educated guesses become more accurate over time.

Experience in the field is a huge advantage

In the example above, Garrett the bike store owner has ample experience with past sales. He doesn’t know accounting or technical forecasting, but he knows his bicycle store and the bicycle business. He’s aware of changes in the market, and his own store’s promotions, and other factors that business owners know. He’s comfortable making educated guesses.

If you don’t personally have the experience, try to find information and make guesses based on the experience of an employee, your mentor, or others you’ve spoken with in your field.

Use past results as a guide

Use results from the recent past if your business has them. Start a forecast by putting last year’s numbers into next year’s forecast, and then focus on what might be different this year from next.

Do you have new opportunities that will make sales grow? New marketing activities, promotions? Then increase the forecast. New competition, and new problems? Nobody wants to forecast decreasing sales, but if that’s likely, you need to deal with it by cutting costs or changing your focus.

Look for drivers

To forecast sales for a new restaurant, first, draw a map of tables and chairs and then estimate how many meals per mealtime at capacity, and in the beginning. It’s not a random number; it’s a matter of how many people come in.

To forecast sales for a new mobile app, you might get data from the Apple and Android mobile app stores about average downloads for different apps. A good web search might also reveal some anecdotal evidence, blog posts, and news stories perhaps, about the ramp-up of existing apps that were successful.

Get those numbers and think about how your case might be different. Maybe you drive downloads with a website, so you can predict traffic on your website from past experience and then assume a percentage of web visitors who will download the app.

Estimate direct costs

Direct costs are also called cost of goods sold (COGS) and per-unit costs. Direct costs are important because they help calculate gross margin, which is used as a basis for comparison in financial benchmarks, and are an instant measure (sales less direct costs) of your underlying profitability.

For example, I know from benchmarks that an average sporting goods store makes a 34 percent gross margin. That means that they spend $66 on average to buy the goods they sell for $100.

Not all businesses have direct costs. Service businesses supposedly don’t have direct costs, so they have a gross margin of 100 percent. That may be true for some professionals like accountants and lawyers, but a lot of services do have direct costs. For example, taxis have gasoline and maintenance. So do airlines.

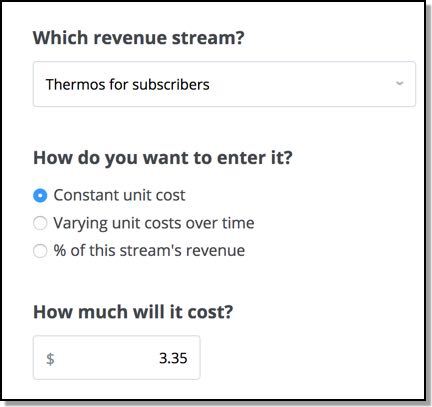

A normal sales forecast includes units, price per unit, sales, direct cost per unit, and direct costs. The math is simple, with the direct costs per unit related to total direct costs the same way price per unit relates to total sales.

Multiply the units projected for any time period by the unit direct costs, and that gives you total direct costs. And here too, assume this view is just a cut-out, it flows to the right. In this example, I projected the direct costs based on the assumption of 68 percent of sales.

For example, In the Soup There It Is plan, the forecast estimates $3.35 per unit for the direct cost of every thermos for subscribers.

Given the unit forecast estimate, the calculation of units times direct costs produces the forecast shown in the illustration below for direct costs for that product.

Never forecast in a vacuum

Never think of your sales forecast in a vacuum. It flows from the strategic action plans with their assumptions, milestones, and metrics. Your marketing milestones affect your sales. Your business offering milestones affect your sales.

When you change milestones—and you will, because all business plans change—you should change your sales forecast to match.

Timing matters

Your sales are supposed to refer to when the ownership changes hands (for products) or when the service is performed (for services). It isn’t a sale when it’s ordered, or promised, or even when it’s contracted.

With proper accrual accounting, it is a sale even if it hasn’t been paid for. With so-called cash-based accounting, by the way, it isn’t a sale until it’s paid for. Accrual is better because it gives you a more accurate picture, unless you’re very small and do all your business, both buying and selling, with cash only.

I know that seems simple, but it’s surprising how many people decide to do something different. The penalty for doing things differently is that then you don’t match the standard, and the bankers, analysts, and investors can’t tell what you meant.

This goes for direct costs, too. The direct costs in your monthly profit and loss statement are supposed to be just the costs associated with that month’s sales. Please notice how, in the examples above, the direct costs for the sample bicycle store are linked to the actual unit sales.

Live with your assumptions

Sales forecasting is not about accurately guessing the future. It’s about laying out your assumptions so you can manage changes effectively as sales and direct costs come out different from what you expected. Use this to adjust your sales forecast and improve your business by making course corrections to deal with what is working and what isn’t.

I believe that even if you do nothing else, by the time you use a sales forecast and review plan versus actual results every month, you are already managing with a business plan. You can’t review actual results without looking at what happened, why, and what to do next.

For more on small business financials, check out these resources:

- The Key Elements of the Financial Plan

- How to Build a Profit and Loss Statement (Income Statement)

- How to Forecast Cash Flow

- Building Your Balance Sheet

- The Difference Between Cash and Profits

If you need some help getting started on your sales forecast and the rest of your business plan, you can try our business plan template, or check out our business planning page.

Do you have questions on how to forecast sales for your business? Let us know by reaching out to us on Facebook or Twitter.

from Bplans Articles https://ift.tt/2S2RG2R

No comments:

Post a Comment